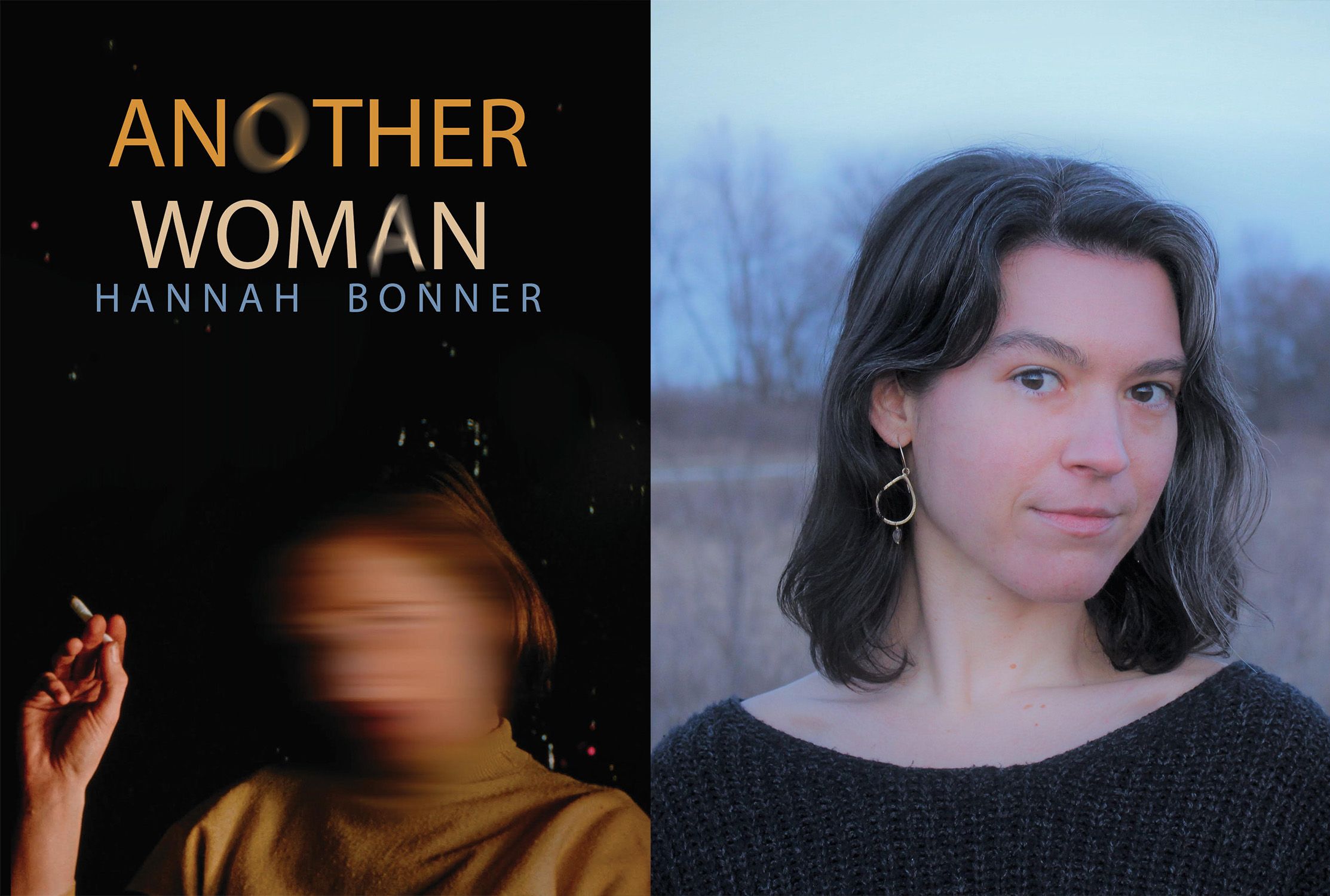

Melissa LaCross: In the introduction to Another Woman, Louisa Hall says, “These poems are about women who experience pain and violence; but…they are also about women who…use language to cut themselves free.” I’m wondering how writing poetry, historically or even this collection, has been a way of freeing yourself or knowing your true self better? Or how does joy and pain weave itself together through language?

Hannah Bonner: When I was writing this collection, it was during the 2020 pandemic, so I didn't think that any of these poems would ever see the light of day, much less be published. There was so much uncertainty during that time that it didn't even occur to me that I was writing a book. I was simply processing a lot of grief and heartache surrounding a relationship with a married man that was entirely on his own terms. Thus, the poems did become a way to "cut myself free," to articulate my own experience and narrative without the pressure of anyone else. Anyone who has ever engaged in an affair knows that the secrecy can be part of the thrill, but that secrecy is also foisted upon you. Not having a say in the ways in which you move through the world can be incredibly destabilizing and demoralizing. Writing, especially poetry, always offers you the choice of self-expression that is especially appealing to me as a woman. There are so many ways, still, in which women politically, socially, and culturally don't have equity and parity. It's self-sustaining for me to write down my story in my own voice. Even if the story is painful, the work and the agency is the pleasure.

ML: Oh yes! I love to hear “the work and the agency is the pleasure.” Can you say more about “the work” and how writing poems to process your experience moved into a realization you were putting together a collection?

HB: When I was beginning to write many of these poems in earnest, I took really long night walks through the rural Iowa landscape all winter long. No matter if there was a snowstorm or rain, I'd set out into the dark to just be alone. There was something magical about distilling what felt like these crushing, enormous emotions against a very vast and open wilderness. After an hour or so I could come home and write until 2 or 3 in the morning. Even though I was heartbroken, and writing from a place of heartbreak, I was working incredibly hard. I'd read every book of poems I could get my hands on: Henri Cole, Mark Strand, Danez Smith, Cynthia Cruz, etc. and those writers became my teachers. They taught me how to edit my line breaks, how to become honest with myself when I was holding on to a line or image I loved because I loved it, not because it served the poem. Doing the work, the real work, which is hard and private can feel overwhelming initially, but once you sink into it -- there's nothing like it for me. When I'm consumed by a poem I feel like I'm possessed. I can't do or think about anything else until the poem has released me. I'm always chasing that feeling.

ML: The idea of night walks is so interesting to me, something I’ve done myself and heard of other writers doing. How do you feel like the wild darkness of the Iowa winter and the act of walking served as a mirror to help you process while literally moving you through the landscape of the relationship and led you to a place of prolific writing?

HB: Night walks attune you to the world in a different way. You're extra attentive to every sound, shadow, and change in color or light. While the hypervigilance (for me, at least) might arise out of a sense of safety, I always finally settle into the space around me and can distinguish what noises are animals and what noises might be another person. This awareness feels so conducive to writing because you're soaking up each and every detail whether it be sight, smell, or touch. I also, at the time I was writing Another Woman, needed a space in which I could be totally abject. Night walks allowed me to cry or wallow in my grief without an audience. To be invisible at night, unobserved and unperceived, was incredibly freeing for me. As women, we're constantly adjusting and readjusting ourselves based on the perceptions of others surrounding us. I want, as much as possible, to exist in a space where I'm the subject and not the object of the looking.

ML: What does Another Woman mean to you, both within regard to the affair but also in regard to the layers of self?

HB: Another Woman obviously plays on the trope of 'the other woman.' But I think the indefinite pronoun 'another' also evokes any interchangeable woman. I wanted there to be a capacious sense of womanhood and femininity within the book, while also articulating my own lived, embodied existence. In this way, 'another' toggles between the hyper specific and subjective with the general. I also believe that I've lived many iterations of my life so far and will (hopefully) have the opportunity to live several more iterations in the future. I haven't been one woman in my life: I've been many. And I'm constantly learning, adjusting, and playing with both the performance of myself as well as the interiority of myself.

ML: It’s interesting how relatable this collection is. Do you think the woman having an affair is a trope, and how were you able to break out of that trope?

HB: I definitely think it's a trope! And it's interesting to me (now, with some hindsight) how amenable I was to performing that trope. Why did I choose to play that role? It certainly didn't benefit me. The man I had an affair with was also my professor, and I think power dynamics always already cast us into prescribed roles. It's incredibly difficult to claw your way out of them, especially if you're the one with less power. He's now involved with another student of his, and that's actually been illuminating to contextualize my experience and realize that everything I went through really was about fantasy, role playing, power, and control for him. Ultimately, I'm not sure if my book breaks out of that trope or not -- I think that's ultimately for the reader to decide. But I did find it important for the "I" throughout the collection to be unapologetic about her experience, to be totally abject when heartbroken, and to ultimately reach a place closer to peace and self-fulfillment than where she began, which is not the same as 'getting over someone.' That relationship inflects everything she sees and does moving forward. But there's forgiveness present now - both towards herself and the "you." I didn't want the book to be about casting blame or judgement on either character -- that's why I chose the Franz Wright epigraph "Rumi says, out beyond ideas / of doing good and evil / there is a field // I'll meet you there."

ML: Your poem, “From Lot’s Wife” joins a lineage of poems about this mysterious woman. What is it that draws us to her untold story and how does your poem join the chorus through the themes of being “Another Woman” or surrounding marriage?

HB: This question reminds me of Rachel Cusk's Outline, how Lot's Wife is a kind of outline, known for her absence rather than her presence. I think women are often socially conditioned to role play and fill in the outlines of whatever someone wants us to be or to perform. So having this archetypal figure that exists without her own perspective appeals to me, in part, because I have, at times, been made to feel like I am "filling in" a kind of role or fantasy for others (most often men). Getting to flesh out a character's interiority feels a lot like acting. I love performing characters on the page, especially from Greek myths or the Old Testament because they demand a kind of gravitas that I don't always feel comfortable performing in my own daily, lived existence.

ML: You have several poems in the collection that act out ancient characters - Delilah, Mary, Dido, etc. How do you feel like drawing from such timeless characters helps the audience empathize with modern dilemmas in a new way or drawing from a new thread?

HB: I think using archetypal figures or characters like Delilah, Mary, Dido, etc. allow us to embrace the depths of our interiorities in ways in which we might not feel permitted to in real life. Having a married man tell me he wanted nothing to do with me anymore didn't end my life -- but it certainly felt, at the time, like my life was over. To say that so baldly doesn't feel poetic, it feels maudlin. But these figures allowed me a kind of gravitas that felt liberatory. I could exaggerate the scale of my feelings, the scope of the story. As women, we're so often taught to be quiet, pleasant, and pleasing. Costuming myself in these characters allowed me to be abject and emotional. I'm thinking of Maggie Nelson's line, "Love is large and monstrous." In this book, I feel like I was large and monstrous, too. I loved that feeling.

ML: The passing of time through the avenue of seasons and rhythms of nature is a thread that runs throughout the collection. How does the continual cycle of nature relate to loss and grief for you?

HB: Grief, for me, is nonlinear. In Stephen Jay Gould’s Time’s Arrow, Time’s Cycle, he writes, “Deep time is so alien that we can really only comprehend it as metaphor.” I think the same is true for grief: we can really only comprehend it as metaphor. So, for me, the seasons sensorially evoke life, death, and all the interstices in between time and time again. I need to cast my own internal landscape against the world in order to put my suffering in perspective or to put my joy in perspective. The Iowa landscape in particular is almost mythical in its vastness -- and incredibly humbling.

ML: How do you write about obvious poetic things like love and nature in a fresh way?

HB: Read ardently. Walk outside as much as possible without your phone. If you're not surprising yourself, it's not the poem.

ML: I love that you say “without your phone.” This feels like such a break from the safety and comfort society we inhabit and brings me to the question: How do you feel technology influences our writing process, both for positive and negative?

HB: I feel like technology is one of the greatest detriments to writing, at least for me. It fractures and monetizes my attention in ways that are not conducive to the sustained attention needed to finish a piece. When I write, I need to declutter my brain. Walking provides the space, time, and silence to think through a poem or essay deliberately and thoughtfully. Also just being in nature opens up possibilities for me, rather than foreclosing them.

ML: Also, in response to surprising yourself while writing, at what point do you feel the poem moves from musings or a rough draft into art? Is it the moment of surprise?

HB: For me, the poem becomes art after the initial spark of the idea. I'll labor over the enjambment, figurative language, word choice, etc. That's work, but it's also fun. I love being consumed by a piece, entirely wrapped up in it. There are only a few things in life that demand that kind of attention from me. Reading widely -- and frequently -- I think allows me to access those moments of surprise more readily. If I'm constantly immersed in the natural world and art, then I'm stretching the muscles I need for when I sit down to do the work.

ML: What were you reading while working on Another Woman? What are you reading now?

HB: I love this question! I always love recommending books. While I was writing Another Woman these books were particularly important to me: Zero at the Bone by Stacie Cassarino, Yes, But by Mark Strand, Second Empire by Richie Hoffman, Postcolonial Love Poem by Natalie Diaz, Guidebooks for the Dead by Cynthia Cruz, Reconnaissance by Carl Phillips, Excerpts from a Secret Prophecy by Joanna Klink, Where Now by Laura Kasischke, Pierce the Skin by Henri Cole, Door in the Mountain by Jean Valentine, and Fieldglass by Catherine Pond.

Lately, the books I've loved have been a real mix of poetry and prose: a student of mine recommended Stone Butch Blues by Leslie Feinberg that I thought was extraordinary. What if the Invader is Beautiful by Louise Mathias felt like reading poetry for the first time - totally breathtaking. I thought Danzy Senna's Colored Television was fun, funny, and wickedly sharp. And then I got two ARCs that everyone needs to read in 2025: Katie Kitamura's Audition and Patrycja Humienik's We Contain Landscapes. Earlier in the fall I reread James Baldwin's Another Country -- that and Plath's The Bell Jar might be tied for my favorite novel ever.

ML: Where do you think your meanderings and walking in nature will take your writing as you move forward from this collection?

HB: Sadly, my evening walks have kind of fallen by the wayside lately. It feels like an old friend I've lost. With so much uncertainty and precarity on the horizon in the coming year, I'm realizing that writing poetry and taking long walks without my phone are more necessary than ever. Making art for my own pleasure feels like a survival tool. And, given how much freelancing I've been doing lately, writing without any expectation for publishing feels like a radical act of joy.