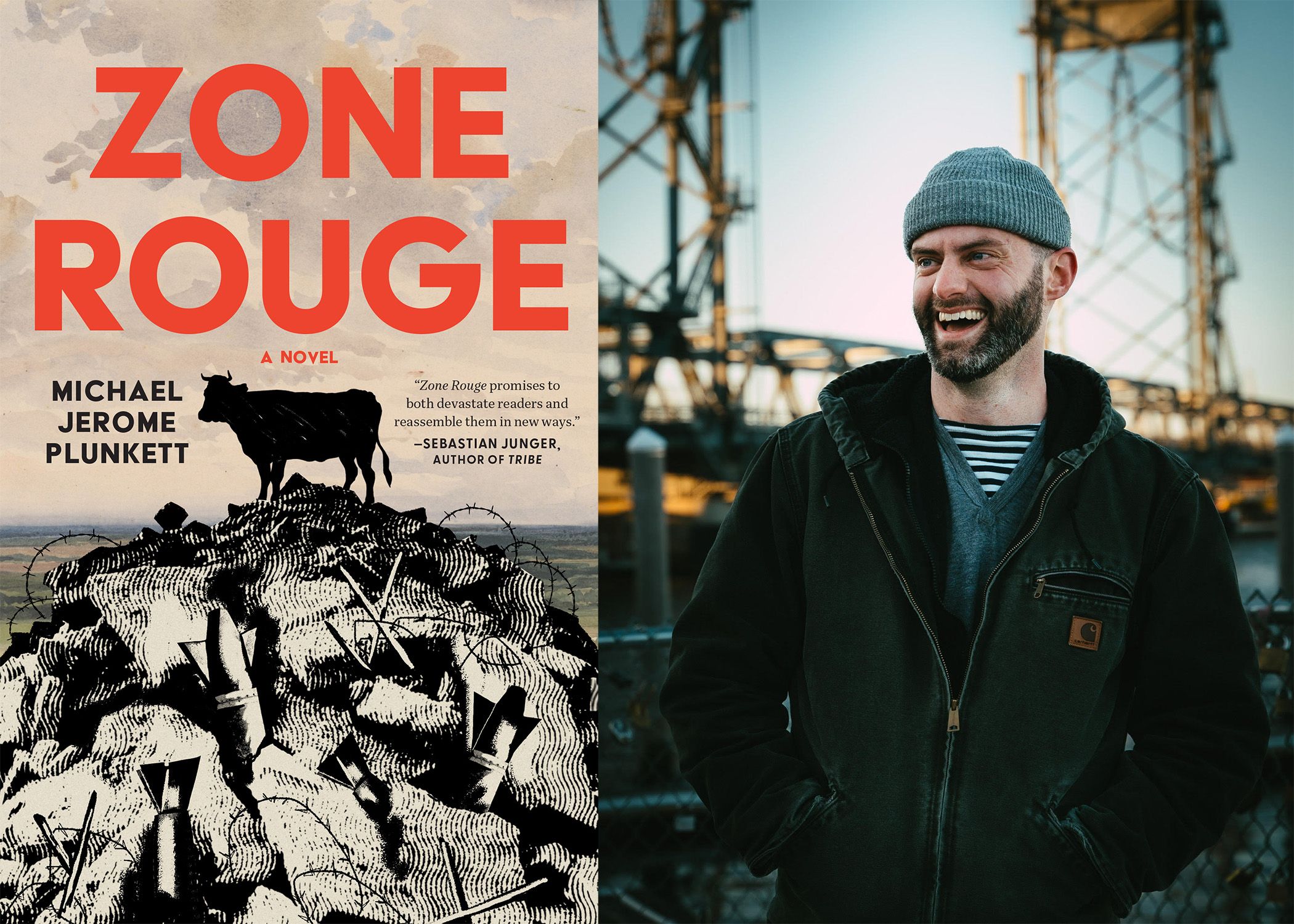

Michael carved out some time on his book tour for me to ask a few questions about his life, the novel’s journey to existence, and the connection between Camus’ philosophical arguments, suicide, and finding purpose and joy amidst the absurdity of life. Below is an excerpt of our conversation.

J. Aaron Courts: Thank you so much for taking some time to speak today. I know you’re busy with the book release, and I realize I’m the small fry on your schedule.

Michael Jerome Plunkett: Thanks for taking the interest, man. I feel like the small fry heading out on the book tour, so it’s pretty nice to be able to know that people are reading the book. It’s kind of wild actually.

JAC: Well, the good news about being the small fry on tour is that a lot of people are going to want to eat the worm. Swallow the hook, people!

First thing’s first. I loved this book. I’m a history buff already, but it hit so many little checks-in-the-box for me as a reader. It’s nuanced. It’s irreverently funny, and it’s obviously tragic, but you do exactly what Jeff Shaara talked about in your interview with him, which is, to entertain, primarily, and spark interest as a result.

JAC: I want to talk about you briefly before we dig into the book. You were an old man for enlistment standards by any branch of service, but definitely the Marine Corps.

MJP: I was twenty-four or twenty-five. Old man of the Marine Corps. When I got to Parris Island, went home for my 10-day leave, then I went back to Camp Lejeune for the Infantry Training Battalion, I was the exact same age of two combat instructors, who were both combat veterans. They weren't just instructors, they had been there, done that. One guy had a Purple Heart and a scar across his face. I mean, just legit. And we’re the same age. Once they figured that out, we compared birthdays, and I was slightly older than them. They didn't look favorably on me. They were like, So, where the fuck have you been…? My nickname throughout that entire school was War Dodger. That's what they called me.

JAC: War Dodger? Wow! How long were you in uniform?

MJP: I ended up doing six years. I moved down to South Carolina to get my MFA, and I transferred down there, finished out my contract, and was out in 2022.

JAC: You’d written a novel while in college that didn’t go anywhere, and then pursued an MFA, but what drew you to writing in the first place?

MJP:I loved my undergrad experience at Gettysburg and had some really amazing professors, but I had a penchant for going for the abstract and experimental. If it was something artsy-fartsy, I would be like, Oh, tell me more. You have my attention. And there was too much of that. In my mid-20s, I decided to stop trying to reinvent the wheel and just tell a simple story in ten pages or less that was engaging and gripping. So, there was a lot of that, and then, Zone Rouge came about.

I took a backpacking trip through Europe. I wanted to see a World War I battlefield. We were taking a long train to Paris, and Verdun was on the way. I get there and come to find that they're still cleaning up all this ordinance. The government has teams that go out, and they have to dispose of this.

So, for 10 years, I was thinking of it, and I tried writing a story. I remember it was such a bad story. It didn't go anywhere. I couldn't even show you a draft. It was just sketches, and I had no idea how to find my way into the story. Fast forward, and I'm transferring from my reserve unit in New York down to Charleston. And you know what it's like working with S1.

JAC:Working with? You mean, putting up with.

MJP: I love those guys, but I had to keep telling them, “I'm literally not gonna be in this state anymore.” I remember the guy handing me the orders. He grew up on Long Island, joined the Marine Corps, and now is stationed back on Long Island. He's got this heavy accent, and he's handing me these orders that are all this archaic language, and there was this interesting dissonance between whomever wrote the orders and the orders this guy has given me.

And I remember driving home thinking, if you've got this team of démineurs, and they're all these guys who've spent time in the military, what does it look like when they have to submit reports? And so, by the time I got to Charleston, I had an idea, and that idea was just to write a kind of an experimental short story. But it was just a collection of after-action reports.

MJP: It was funny and fun but not sustainable for a whole novel. And that was how Zone Rouge started. It was literally just like that. This very formatted, heavy, heavy report.

JAC: That’s great. I love that an epistolary form is at the heart of this novel. Let’s shift gears and talk about why you incorporated a retelling of The Myth of Sisyphus into your interest in Verdun. Why Sisyphus? And did it all begin with the Greek mythology or Camus?

MJP: One of the first things that came to me was the [démineurs’] job is never going to be done in their lifetimes. Most days are boring. A lot of the shells have degraded. They're in pieces. They're not necessarily dangerous, but every now and again, one of them still blows up, and these guys were moving them around. They stockpile them in places, and they move them from one room to another, and something blows up. And that’s what it is like being in a profession where you're doing your job, and nobody's gonna thank you for it, and you're never gonna see the end of it, and it's pretty boring. But once in a while, you might get killed doing it.

Instantly, I thought of the Greek myth of Sisyphus. I didn't know very much about it. I just knew there was a boulder, he pushes it, and it rolls back down. That was when I stumbled upon Camus' interpretation. A lot of people say the myth represents this mundane existence where it’s a punishment. That's what Sisyphus has been condemned to do.

Camus flips it on his head and says, [Sisyphus] has agency over his fate. He actually makes the decision to turn around at the top of that hill and walk back down. Nobody's making him do that. And that was one of those moments where I was seeing things completely differently.

MJP: I'm not an expert, but there was such a sarcastic, postmodernist, kind of ironic attitude toward so many things, where everything was meaningless. There was a lot of, institutions are meaningless, things are meaningless, and that was hanging over a lot of contemporary literature I was reading. And I think it had started to bleed into some of my stories, and I did not like that attitude past a certain point. I could not get much out of it.

JAC: I think that comes through. How did you decide between what aspects of both to put in the novel, because you have the reimagining aspect of the boulder to the artillery pieces themselves. That's a very direct sort of reimagining. And then there’s the repurposing of stuff from Camus.

MJP: Great question. The challenge with Martin was deciding when we’d reach a point where it no longer felt real? He’s just had such a hard life, so much tragedy. At what point will people start rolling their eyes and thinking it’s a little melodramatic. I was really trying to balance that.

JAC: You’ve got several career fields featured in this novel. Tell me a little bit about the type of research you did specific to some of the technical stuff we read about.

MJP: You know, it's funny. So, going back to that Civil War novel, one of the things I wanted to do differently, was to not overdo the research. The goal here is to tell the story I'm interested in. It's not to educate people on Verdun.

JAC: Did your experiences in the Corps help with respect to your research?

MJP: Even in the military, throwing a couple grenades was the extent of my explosive experience. But I do know about being on a truck, shift work. I was an EMT in South Carolina while I was in my MFA program.

I start thinking, in some ways, [démineurs] are completely different, but I can tell you about being an EMT. Most days are pretty boring, pretty slow, and then all of a sudden you have this life-changing experience, or this crazy adrenaline rush, and then it's funny. You go back, and then it's like, alright, what do you want to get for lunch? I don't know what it's like to disarm or to dispose of one of these 75mm artillery shells, but I know what it's like to have a profession that's similar to that.

JAC: That makes a ton of sense. I want to dial back into the book more directly. Let’s talk about the humor and the sex in Zone Rouge. How did you decide how much irreverent mil-humor and sex to put in there? Because, as you well know, a veteran’s sense of humor is off from everybody else's, and a Marine's sense of humor is way off.

MJP: When I started writing the novel, I didn't have a book deal or anything, and I had no idea. What's funny is none of that stuff was in until the last two drafts. I don't know if I was intentionally walking some kind of tightrope or trying not to turn anybody off by putting some weird sex stuff in there.

There was a sex scene, but it ended with them kissing in the darkness with some flowery language alluding to the fact. And I thought it was being a little too safe. Where's all the irreverence, and the sex, and the people getting blown to pieces, and people having to scrape them up? You gotta bring some of that in. This might be my one chance. There's no guarantee of a second book. And I thought, if I'm gonna do it, I'm not gonna have anybody accusing me of being too timid.

JAC: You wanted to Plunkett it? To Plunk-it!

JAC: As with Camus’ essay, your novel touches on suicide. I think one of the more meaningful sentences in the entire novel is “god failed us,” both semantically and syntactically, in large part because of its deviation from grammar norms. But I’m thinking about what the Corps refers to as “spiritual fitness.” Given the service’s acknowledged importance of spiritual fitness, and the understanding that so many active-duty military and veterans successfully suicide each year, do you think those syntactic and semantic choices—that sentence—challenges our notions of spiritual fitness or is it possible that it motivates us to think about spiritual fitness in different, more accessible ways?

MJP: Well, specifically for that little line, nobody knows who says it. It's just there. It could have been anyone. Any one of the démineurs. It’s supposed to just kind of be hanging there, almost as if it just appeared, you know?

From a personal standpoint, I didn’t want the story to be pessimistic and hopeless. And it could very easily turn into that. But in the act of doing, these guys are able to find some type of meaning. Not all of them. And that's what I want it to be. There's a spiritual component. It's this idea of handling these questions. What do you have agency over? What do you have control over? Taking it one day at a time, one step at a time, and that was something I kept coming back to.

JAC: Do you believe The Myth of Sisyphus and Camus' philosophy there allows Marines to fully engage in spiritual fitness? Can we embrace the absurdity that Camus is talking about and find joy in the individual acts we take? Can those things be done at the same time?

MJP: I think you have to do both. Since the time I started Zone Rouge, six major wars have broken out all over the world.

It’s kind of crazy to me to think that Ukraine has now become the world's largest minefield. All those artillery shells that are currently in the soil in Ukraine are gonna take billions of dollars and decades to remove. They weren't there when I started writing this novel.

The world is an absurd place, and sometimes when I hear people say “it's all hopeless,” I'm thinking it's always been this way in some form or another. And, once again, if you allow that to get into your head, it can get dark quickly. For me, I know it can. You need to be aware of the absurdity. But I also think it's possible to exercise some type of control over that within your own realm.

That can look like different things to different people, but it’s possible if you have that sense of purpose. If you can identify that—if you're engaging with what that means to you—you can find a bedrock that you can hold onto. I really do believe that.

JAC: Was any part of this written for the purpose of helping folks with that sort of struggle?

MJP: Of course. Probably not directly trying to help people. I don't know if I approach stories that way. Novels have the potential to hold so much. They're about getting your elbow room and being able to spread out and kind of move around and explore and see what that looks like. I do hope that people read Zone Rouge and realize that you do have personal agency, over this, even if it is just picking up one shell at a time and showing up, day in-day out.