Casper Orr: You just had your first collection published this May, which was written with a lot of fantasy and fairy tale elements. What’s your background with fairy tales? What role do they still have in your life?

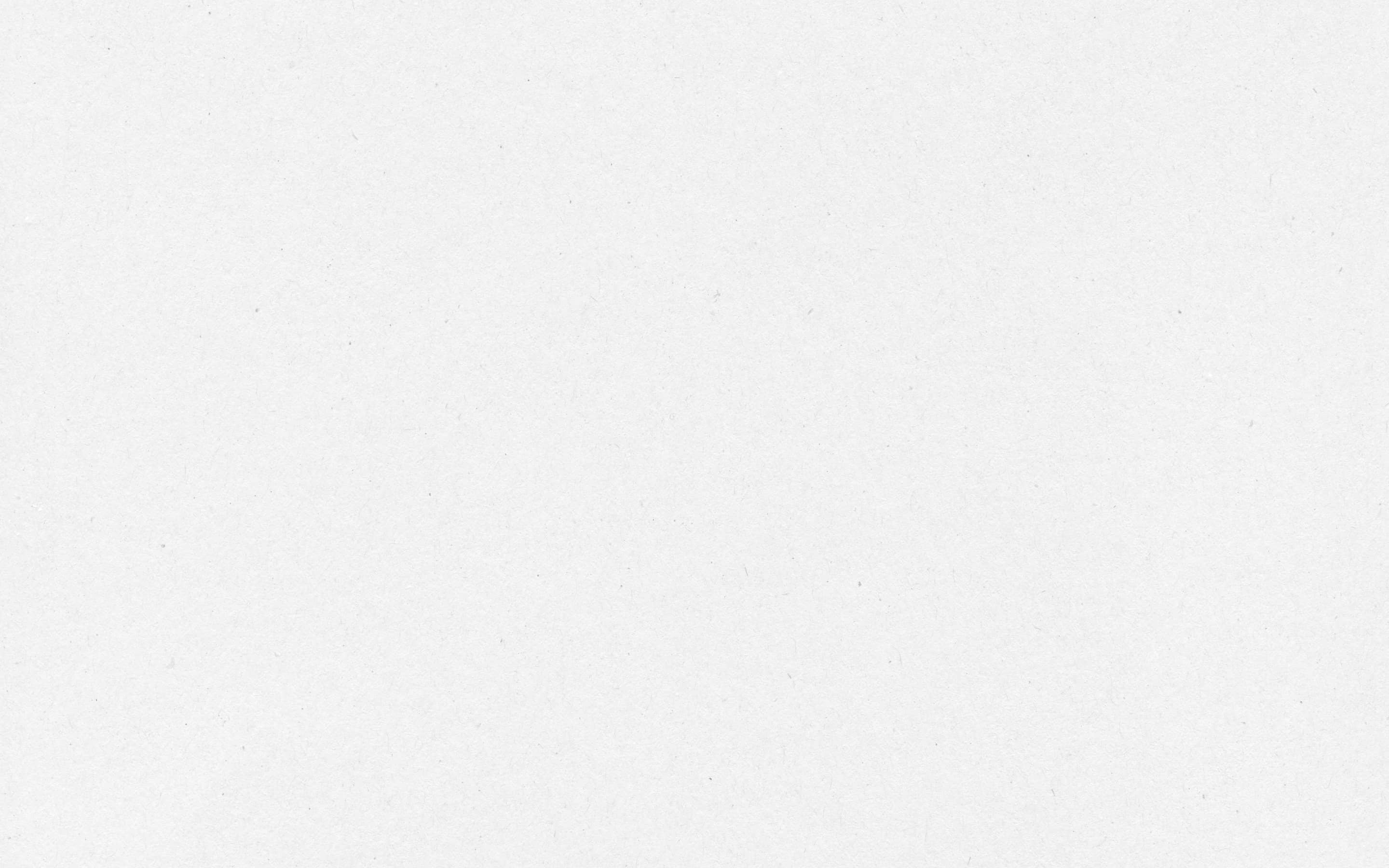

Molly Olguín: I have always loved fairy tales. As a little kid, I really loved the Disney retellings. I was also one of those kids who was a voracious reader, and kids get access to a lot of fairy tale books. I really just lived in those worlds growing up, so I feel like the form has always stayed with me as a fun thing to play with.

I had parents who would tell [them] aloud, so I got to hear the stories and retell them to my sister or my cousins, [got to] have that feeling of participating in this tradition. It's like a really big group story that you get to be part of. I think that’s part of the fascination.

CO: Fairy tales are such a participatory activity. Do you have a favorite fairy tale?

MO: I feel like I should say my favorite is The Little Mermaid because it comes into my book, but my absolute favorite story growing up was Beauty and the Beast…Something about the idea of the monster that you fall in love with has this timeless appeal. Obviously, there's the abuse narrative in Beauty and the Beast. There's also this idea of having to look beneath the surface of a person that you think is the villain, but actually they're also trapped in this haunted castle in the woods.

CO: Judgement based on appearance and social perception is a theme that comes up a lot in fairy tales—like Beauty and the Beast and Princess and the Frog. Not so much looking at each other shallowly, but seeing each other with more nuance. Fairy tales aren't so black and white.

MO: Oh, totally. The thing I love about a fairy tale retelling is that you have these very flat, sort of archetypal characters. It's possible to breathe all kinds of different life into them and to have all of it feel correct, because you've got such a flat baseline. I think that level of complexity and nuance gets to be reinvented by every new storyteller, and that's really exciting.

CO: You bring up something that we’re seeing more and more with modern fairy tale adaptations in pop culture. What do you think is changing in the narratives and the storytellers that are prominent in fairy tale retellings?

MO: I think there's so many ways to answer that question. As stories change over time, we have different people telling stories in general. The fairy tales that I was growing up with tended to be the most popular stories out of the Grimm's fairy tales or Blue Book of Fairies.

That sort of singular European vision of what a fairy tale is, was very predominant in the ‘90s. I think you definitely have more people playing with those popular European fairy tales, because a lot of people grew up with them and made them our own. You have people like Helen Oyeyemi—[she’s] really playing with the style, texture, and structure of fairy tales, [while] still telling completely original stories. I love her collection What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours. I think there's really exciting things people get to do with tropes that feel familiar, but make them unfamiliar because it's new people telling the stories.

CO: When I was reading your collection, I remember trying to read it through the lens of a retelling. Initially, “Seven Deaths” reminded me of “The Juniper Tree.” Are these stories based on classic fairy tales or are they completely your own creations?

MO: [I] describe it as the seeds of family stories sprinkled into the soil of fairy tales. There's a bunch of stories in the collection that spring from family [lore that you’re told] over and over again as a child. I'm sure some of this happened, but it cannot all have happened this way. I think you have a little skeptical part of your childhood. I think the older I get, the more I'm like, “Okay, that is true because it's trying to describe a feeling or an experience that is impossible to describe.” So, it takes on this sort of magical hue.

“The Seven Deaths of The Family Contreras” is a family fairy tale. Most of the things that happen in “The Seven Deaths” are things that happened to my family—perhaps not quite as literally—but also a thing can be true and not be literally true.

CO: The idea of personal fairy tales is so niche, but it's so intriguing. It reminds me immediately of your one story, “Captain America's Missing Fingers.” I think when we think of fairy tales, we think of something that is so widespread that we don't consider that it can be so personal.

MO: I'm so glad you brought up “Captain America's Missing Fingers,” because that is another one of the stories in the collection that comes from real life. The first story that the grandpa tells about the ice cream is one of my family legends. I took the root of that story and built the rest around it.

This is not a family story that made it into the book, but there's a story in my family: unto every generation, there will be born two sisters. One will be beautiful, and the other will be ugly. The beautiful one, she will marry, and the ugly one, she will serve the family. I truly heard the story and I was like, “This is a fairy tale. A weird little family curse.” It was a way to talk about this experience of a mail order bride in our family history. How do you talk about the mail order bride bringing her sister with her?

CO: Your collection told a lot of really unique perspectives on identity through a magical lens. A lot of the stories had characters that were of queer, Hispanic, or immigrant backgrounds. Is there a reason that you are drawn towards telling these stories with magical elements?

MO: I think the easiest answer is that I'm the one telling these stories and I'm queer and mixed race. I kept going back to [stories] like, “Okay this feels like a fairy tale.” It feels weird because they're a really [unique] form. They don't really help you explain the world. They don't necessarily have a moral, although some of them have morals kind of added on.

You brought up “The Juniper Tree.” It’s just fucked. Fucked up shit happens in life, that’s what “The Juniper Tree” is about. And you just kind of have to accept this weird shit that happens.

I think that's why I was looking at that framework.

CO: A lot of fairy tales don't have a moral code, but in their original form, they're usually just forms of emotional processing. I think that's what makes folklore and fairy tales so interesting. At the same time, I think fairy tales have also been so heteronormative and nationalistic, depending on where they're being told or written, so to see queer and more diverse perspectives is really great.

MO: It is definitely a thing that I really love to read. All writing is in some way, not necessarily about yourself, but from yourself. In one way, I'm just writing for myself. And in another way, I'm 100% writing the stuff I am most excited to read.

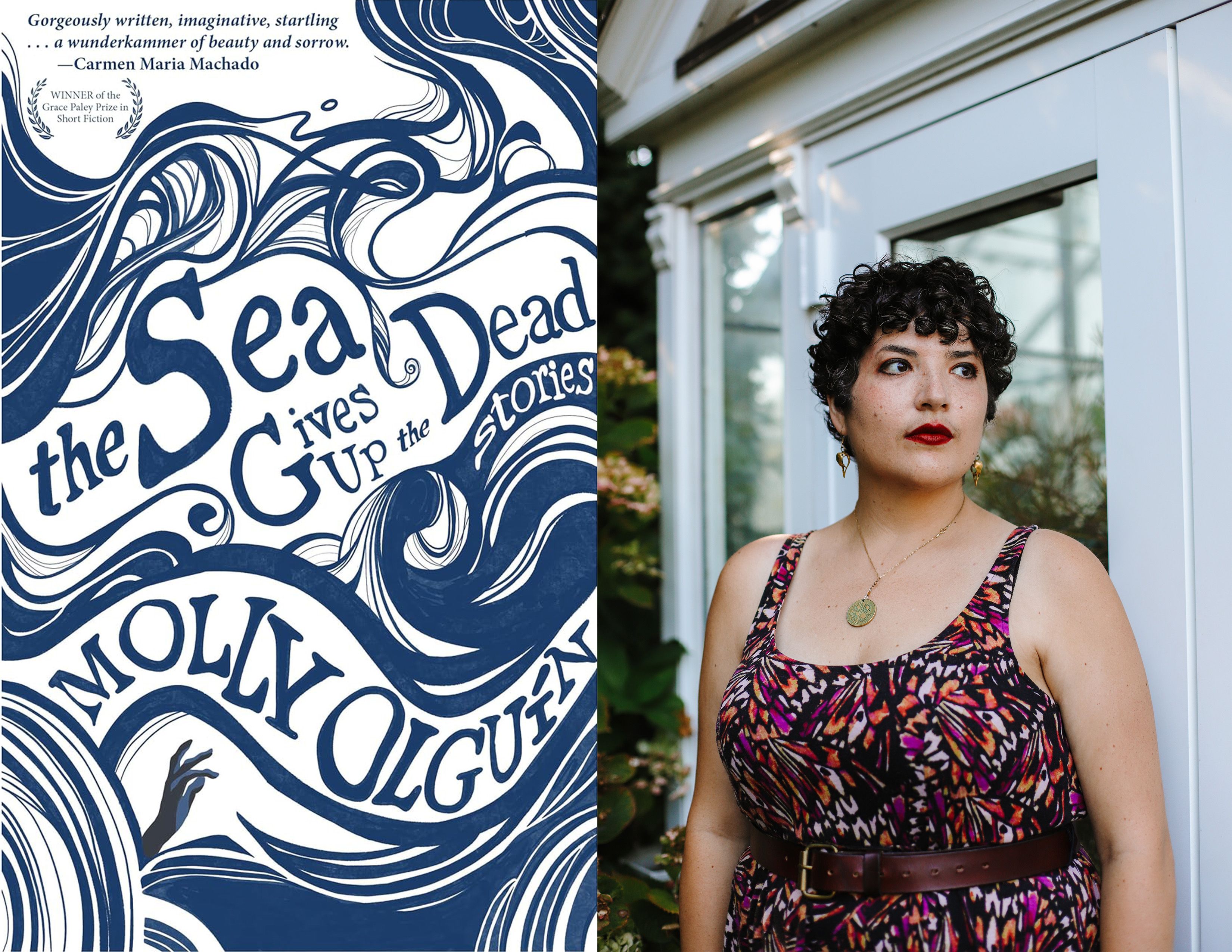

CO: You named this collection after your second to last story, “The Sea Gives Up the Dead.” Why did you choose that specific story to name your collection after?

MO: There's a longer answer to this question. Most of the stories that I wrote, I wrote a long time ago for my MFA thesis. At the time, I did not have that story. I was looking at the themes and [trying to ask], “What really ties this all together?” I've got a lot of stories about people returning from death in one way or another, a lot of stories about the sea, a couple of stories about drowned girls returning from the sea.

I have this sort of uneasy relationship with Catholicism throughout. So obviously, I went looking for Bible quotes. I found the book of Revelation, this description of when the apocalypse happens, the sea will give up the dead. I really loved that. That's an evocative line. I like it being about the literal apocalypse. A revelation is both to learn something new and also to have everything end with this big moment of death, but it's also a moment of transformation. I felt like it tied up a lot of the themes of the book together.

The last story I wrote was another story about a sea voyage and then a girl who comes back from the dead. There was no other title but The Sea Gives Up the Dead for this collection, which felt very weird to do having already had the title for the collection. It just had to be.

CO: You mentioned it took you a while to get all of these stories written to compile the collection, which is definitely in the spirit of the fairy tale. How long did it take you? Did you have people helping edit and read with you?

MO: I wrote most of these stories for my MFA thesis. During the MFA, I had a ton of help working on things. At the end of the MFA, I had this feeling like, “Actually, I don't think it's good.” I think that comes from the weird fact that writing is a psychological game. I'm really trying to remember this for later. The way I felt about it did not actually have any relationship with how good the work was or was not.

In an MFA program, you're getting a lot of feedback. Maybe it's helpful, but maybe it's overwhelming. That's going to make you feel a certain kind of way about your work. I really needed the space away from the MFA to be able to take a second look at this book. The stories that I wrote later in the process, I had a couple of trusted readers that I was going back to, but it wasn't the same level of drafting that I was doing for the earlier stories.

CO: Do you have plans for what's next?

MO: Yes, I actually finished a draft of a second collection just a couple days ago. This is a project that I'm really grateful to have had support from the Jack Hazard Writing Fellowship. It's a fellowship for high school teachers who are also writers, so if any of you reading this interview are high school teachers, you should definitely apply for the Jack Hazard Fellowship.

I just finished this draft of a second collection that I'm really excited about. It's not going to be strictly another book of fairy tales, but a book that I'm calling “literary fanfiction.” Each story is an adaptation, transformative work, or retelling of some kind. And I do have a Beauty and the Beast retelling in the mix.