Montserrat Andrée Carty: Let’s begin by talking about structure! I love how your book moves between forms and genres including epistolary, photography, poetry and short stories. Can you talk about the process of blending and bending form within a book?

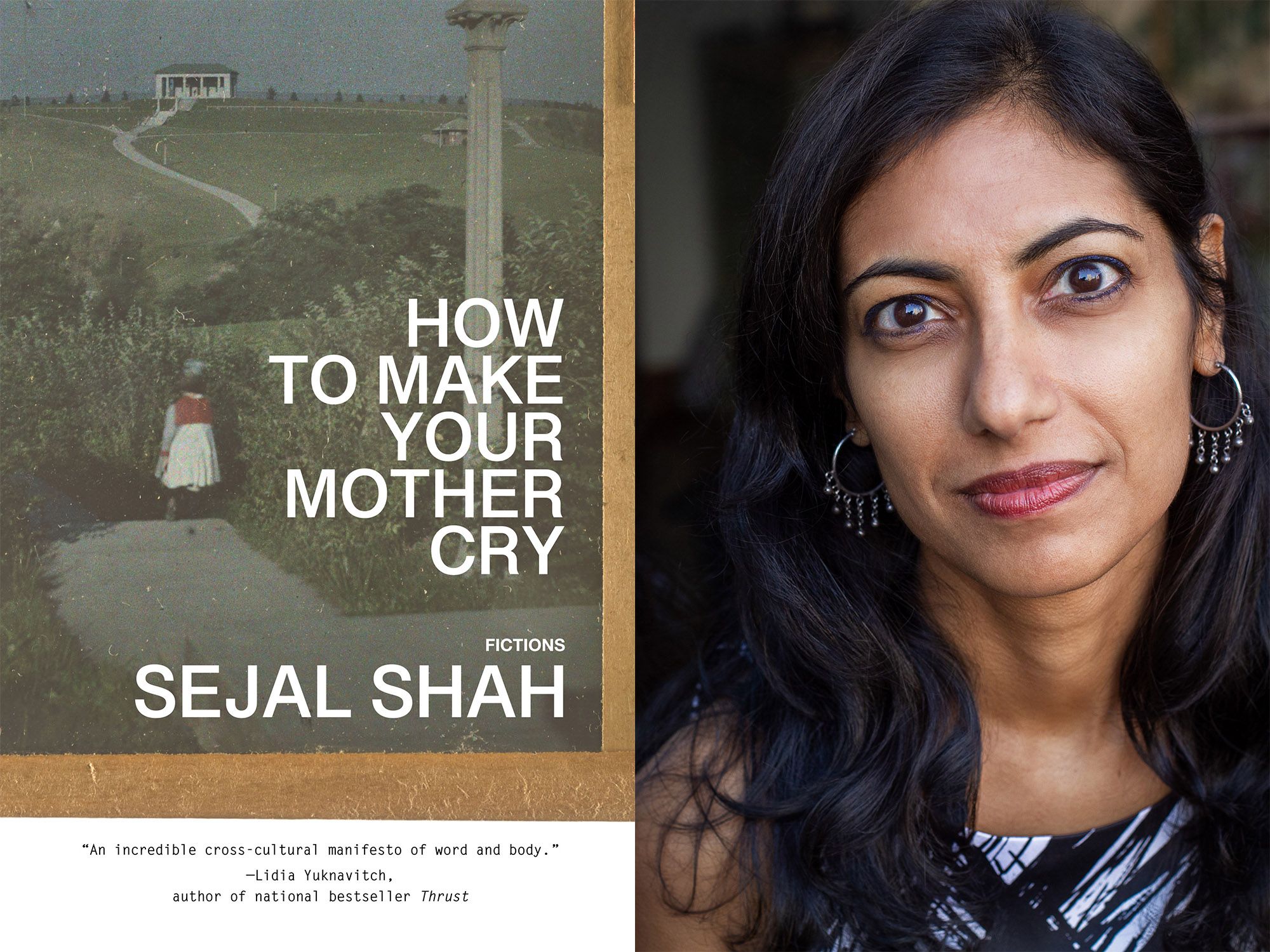

Sejal Shah: Structure has always been fascinating to me and also a challenge. How to Make Your Mother Cry is a book where it was absolutely both. For a long time, my book consisted of eleven short stories separated by ten brief letters I call “Letters I Never Sent.” That original manuscript came close to being published: it was a finalist at contests at Sarabande Press and Pleiades Press. However, I set the stories aside when my essay collection found a publisher and I worked on the essays that would become my first book, This Is One Way to Dance.

By the time I returned to the stories, I had an agent who was interested in representing them. She asked if I had any additional stories. I said no, but I had been interested in adding images. My agent loved the idea and I began to look through dozens of images that resonated in some way for me. Originally, the manuscript contained no poems. As I continued to revise, I added “The Granite State,” my ghazal about journalist James W. Foley, who was my graduate school friend and classmate. My editor suggested taking out the poem, because it didn’t necessarily fit: including a poem broke the established pattern of story, letter, story, letter. However, I felt strongly that the poem should stay. Instead of removing it, I ended up adding three more poems. I was asking the reader to do a lot, moving from form to form, so I also added some scaffolding–dividing the book into three titled sections: I. a girl walks into the forest; II. a girl is lost in the woods; and III. a girl claws her way out. I hoped this scaffolding and structure would offer the reader some thematic landmarks in a book that bends and blends genre and doesn’t follow a typical format for a story collection.

MAC: I love the inclusion of images and ephemera in the collection and wanted to hear more about that. You note that the images are not illustrations of the text. What was your process for selecting and then sequencing the images between the text?

SS: I lived with these stories for many years, so I had time to think about the symbols and imagery within them as well as some of the images from my life that felt as if they had some resonance with the stories. I chose ephemera and images that felt as if they had some sort of associative relationship to the stories. My process included printing the manuscript and moving images and ephemera around on my living room floor, trying to discern an order that made sense. It was almost like laying objects near each other and seeing where and how they magnetized. I was looking for energy vibrations, seeing what felt like it “landed” based on where the images were placed. I also had many conversations with my assistant and collaborator Abbey Frederick, a talented poet, about how the images were speaking to each other and to the text.

I think of the images and ephemera as creating poetic pauses. The images work to weave their own narrative throughout the book, a secondary narrative that is juxtaposed with the stories. These artifacts are often personal. As you said, they are not meant to be illustrative of any of the stories, but rather to provide a kind of visual echo of some of the themes in the stories and poems. I also simply liked the artifacts and wanted to carry them with me into the art of this book.

MAC: How do you know what form a particular piece will take? Do you tend to know from the start (i.e. I am writing this as a poem) or is it more a process of discovery that occurs as you are in the middle of writing a piece?

SS: I think I’ve had both experiences: one where I know what I am writing is, for example, an essay, and other cases where I am just writing and then after the writing, I see what has come out and I work on shaping it. So it’s a process of discovery. Other times I’ve gone into the process with a form or idea in mind. Either way, I do believe that the writing will tell you what it wants to be if you listen.

MAC: You say “Writing is something I’ve always done. Publishing and preparing a book for publication is a whole other thing.” Can you talk a bit more about this and what tools you use to prepare yourself mentally for publication?

SS: Honestly, I think publication is a really hard process, which is maybe ironic because it’s what most of us want or many of us want, but the process of writing is so private and exploratory. Publishing means it’s a conversation with the wider world and involves other people’s ideas and feedback and sometimes pushback. Thank God for editors and agents, press directors and art designers, copyeditors, and all of the people whose work goes into making a book, but there are moments where it is a lot of steps that are far from the original impulse to write. Publicity and marketing are even further away from the original creative impulse, though I think one can find creative approaches to both. In terms of what tools I use to prepare myself for publication, I wish I had a better answer for this. Meditation and yoga are really helpful, as is taking things one step at a time. If you look at too many steps at once, I think it can become overwhelming.

You are moving from a process that at least for me is more working via instinct to one that involves a more rational, left-brained approach so it’s the other side of the creative process, but it sometimes (often?) is challenging. I say that even while also wanting to emphasize how grateful I am to have had the opportunity to publish my work.

MAC: Dance seems to be such a big part of your life. Can you tell us about the way dance informs/influences your writing or vice versa?

SS: I grew up dancing from the age of four so really I came into language (reading and writing) and movement at the same age, at the same time, and for me they are inextricably linked. I think movement in all forms is important and walking for me is also really important to my process as a writer, with integrating the kind of leaps I’m making in my thinking and writing. When I was working on How to Make Your Mother Cry, I danced to a lot of songs on repeat, and some of those songs are listed in the soundtrack at the beginning of the book. The songs and the dancing were that important to the book! This was during the pandemic. Dancing was a way to move in space and to connect to others as I did these dances at home on my own and posted them on Instagram. These dances connected with other people and gave me feedback in a sense (through friends’ comments) that I was moving in the right direction with how I was thinking about my book.

MAC: It was great to see your list of “companion texts” listed at the end. What a fantastic list! I wonder if you could name a few authors whose work, like your own, crosses form and genre that you especially love?

SS: I was inspired by Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric, Citizen: An American Lyric, and her latest book, Just Us: An American Conversation. I have also always admired Leslie Marmon Silko’s Storyteller, which consists of prose, poems, and photographs. More recently, I have loved Alice Wong’s memoir, Year of the Tiger: An Activist’s Life and Gabrielle Civil’s The Déjà Vu: Black Dreams & Black Time.