The girl has begun to stomp sidewalk anthills

with her delicate and dimly probing feet.

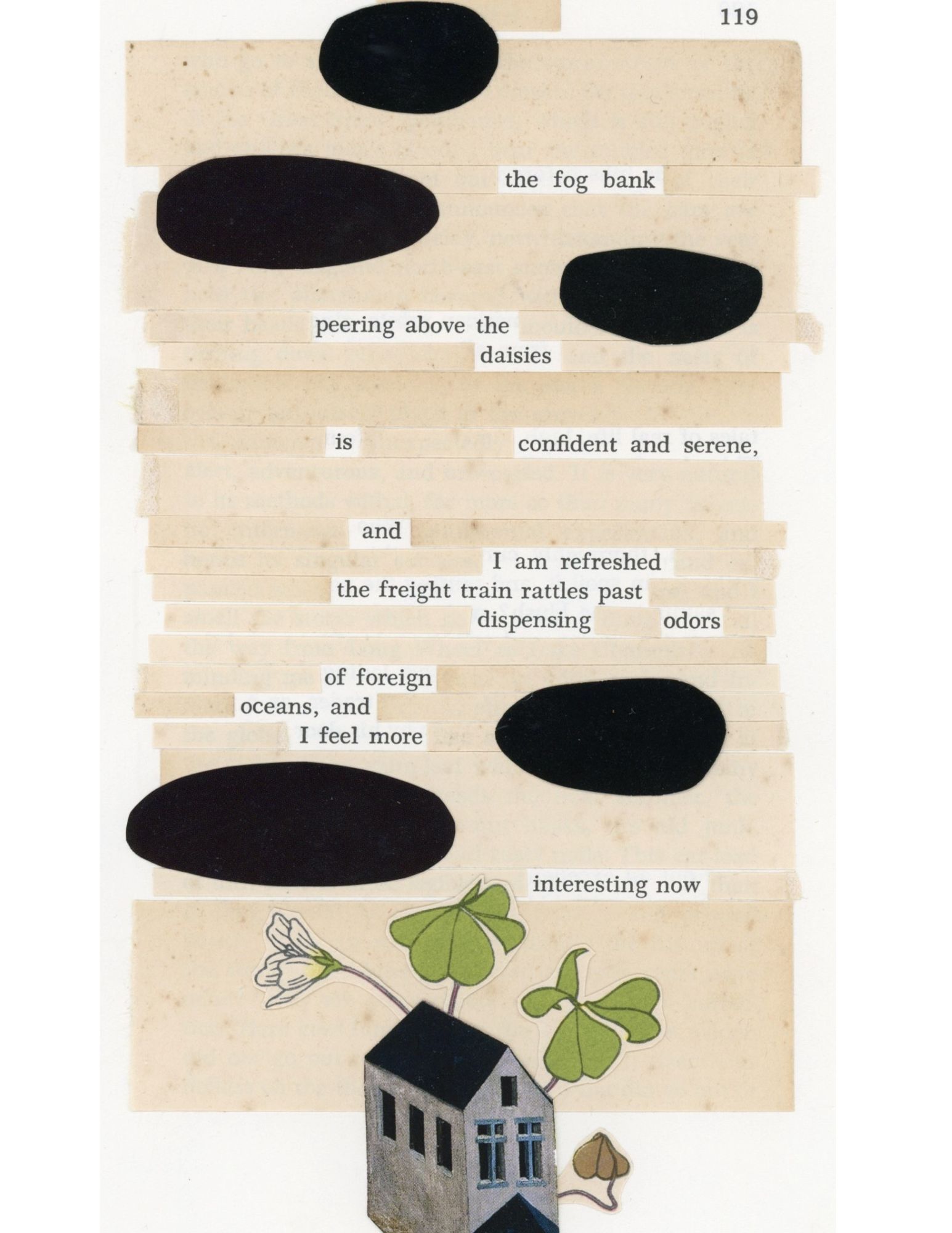

Bewildered insects swarm like static

broadcast through destroyed cities.

I’m thinking of actual cities, of Orson Welles

and his radioed apocalypse driving families

frantic into the street with damp rags pressed

to their mouths. And nothing but a low-hung sky

when they get there. Nothing but the last

tired clutches of autumn, a kestrel casing

the cul-de-sac. If they were afraid of losing

something then it was because this was the first time

they realized they had it. It’s baffling how used

to being alive you can get. When I was her age

I watched fields pull past the school bus window

and wanted to know something about how

other people did it: the tall boy committing

a summer to his neighborhood’s lawns for some

indecipherable hourly rate, a bank teller engrossed

in opening rituals, someone prepping vegetables

in a strip mall pizza closet. From beneath each

of their sweat-lacquered brows, embossed awnings,

cursive neon placards: I’m still looking up. In Babel

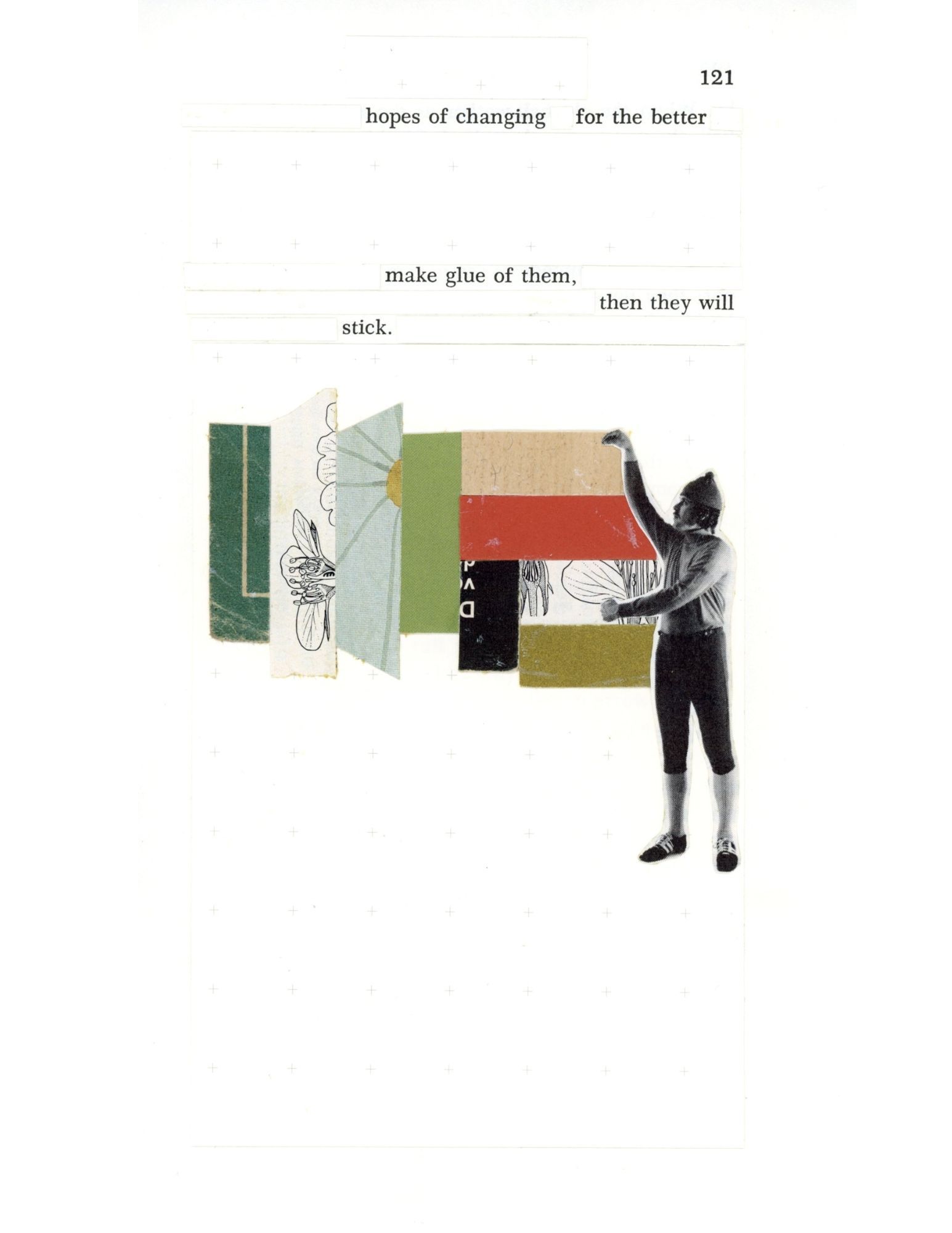

it was the tower, destroyed because no one

who wanted it could understand one another.

No one could stop their fevered bricklaying, turn

to whomever at their shoulder and say Yes. I believe

this can be as great as you do. But we’re mired

on this sidewalk in our parallel backstrokes through

responsibility. And I love her, this girl who looks up

as if to ask me to tell her what she’s doing. Or to stop.

But I am drawn away toward the sky, a fresco

of gathering clouds. She tugs my sleeve to turn,

an alley—we’re on our way to destroy something else

by misunderstanding it. Her pink galoshes

map a mess to the maw of the storm.

Jess Williard

Author

Jess Williard is the author of Unmanly Grief (University of Arkansas Press, 2019).